POST

HISTORY OF CYBER

390BC -342BC: The START

Κυβερvνητική

Cyber is derived from the Greek κυβερ, which means “to steer, to discipline or to govern”.1

One of the most prominent uses of ‘cyber’ in Greek literature is in Plato’s First Alcibiades. There the metaphor of κυβερνήτης (steersman/pilot) is essentially used to summarize “the entirety of Greek philosophy, integrating Mythos, Logos and Nomos”.2 It relates to “thought-aided, purpose-directed, history-illuminated, feedback-dependent, and future-affirming or feedforward-sensitive governance”.3

1 jerry Everard, Virtual States: The Internet and the Boundaries of the Nation-State (New York: Routledge, 2000). p. 15. 2 Barnabas Johnson, “The Cybernetics of Society: The Governance of Self and Civilization,” jurlandia.org/cybsocsum.htm (accessed October 30, 2013). 3 Johnson, “The Cybernetics of Society: The Governance of Self and Civilization”.

Cybernétique

Art of Governing

Coined by André-Marie Ampère in 1843 in his book Essai sur La Philosophie des Sciences. Ampère suggests that the term “[…] dans une acception restreinte“ relates to “l’art de gouverner un vaisseau”.1 But, he states that even the Greek interpreted it more broadly, “reçut de l’usage, chez les Grecs même, la signification, tout autrement étendue, de l’art de gouverner en général“.2 In other words, Ampère understands the term to relate to the art of governing.

1 André-Marie Ampère, Essai Sur La Philosophie Des Sciences Ou Exposition Analytique d’Une Classification Naturelle De Toutes Les Connaissances Humaines (Paris: Bachelier, 1843).

2 Ampère, Essai Sur La Philosophie Des Sciences.

Rise of ‘modern’ computers

See for example:

The Atanasoff–Berry Computer (1937-1942), Z3 Zuse (1941), Colossus (1943-1945) and Eniac (1945).

Cybernetics

Cybernetics

“control and communication whether in the machine or in the animal”.1

Cyber as a prefix gained wide attention due to Norbert Wiener’s 1948 book Cybernetics. He uses cybernetics to describe “the entire field of control and communication theory, whether in the machine or in the animal”.2 Wiener is said to derive the term from Greek language, though it could also be the Anglicization of the French term ‘cybernétique’.

1 Norbert Wiener, The Cybernetics of Society: The Governance of Self and Civilization (Cambridge: M.I.T. Press, 1948)

2 Wiener, The Cybernetics of Society.

First packet-switching network

First packet-switching network

“Who invented packet switching? Like the development of hypertext, packet switching seems to have been an idea that wanted to be discovered. The packet switching concept was first invented by Paul Baran in the early 1960’s, and then independently a few years later by Donald Davies. Leonard Kleinrock conducted early research in the related field of digital message switching, and helped build the ARPANET, the world’s first packet switching network.”1

1Living Internet. (2000). Packet Switching History. Retrieved from livinginternet.com/i/iw_packet_inv.htm.

First use of ‘Cyberspace’

Art and ‘cyberspace’

Cyberspace’ was first used by the Danish artist duo Susanne Ussing and Carsten Hoff in 1968 to 1970. For them ‘cyberspace’ “was simply about managing spaces. There was nothing esoteric about it. Nothing digital, either. It was just a tool. The space was concrete, physical.”1

1 Jacob Lillemose and Mathias Kryger, “The (Re)Invention of Cyberspace,” Kunstkritikk, kunstkritikk.com/kommentar/the-reinvention-of-cyberspace/ (accessed October 18, 2017).

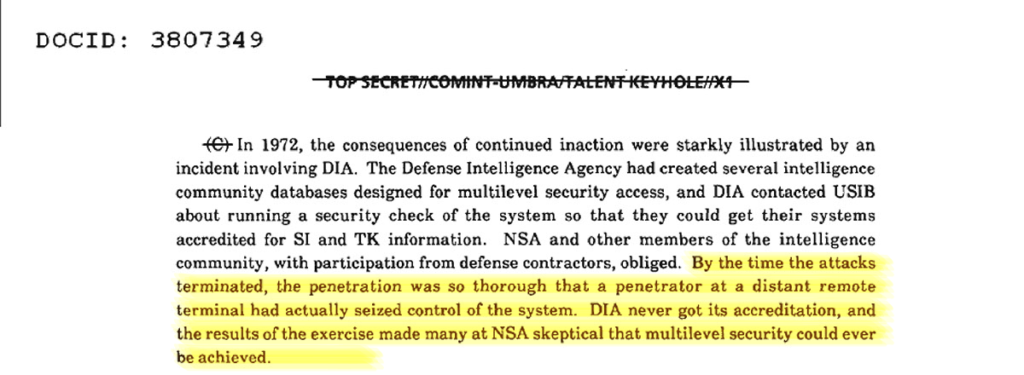

Information security becoming problematic

Wake up call?

In trying to accredit intelligence databases for multilevel access,1 the Defence Intelligence Agency requested a “security check of the system so that they could get their systems accredited for SI and TK [signals intelligence and Talent Keyhole/top secret] information”.2 The result of the exercise can be best summarised by the following quote: “By the time the attacks terminated, the penetration was so thorough that a penetrator at a distant remote terminal had actually seized control of the system. [The Defence Intelligence Agency] never got its accreditation, and the results of the exercise made many at NSA sceptical that multilevel security could ever be achieved”.3 Similarly within the United States Air Force, teams testing the vulnerability of systems (so-called ‘tiger teams’) concluded in 1979: “In a very real sense the Air Force has been fortunate that security is so poor in current computers – the greater danger will come when the argument that a computer is secure because tiger teams failed to penetrate it appears plausible”.4

1 Thomas R. Johnson, American Cryptology during the Cold War, 1945-1989: Book IV Cryptologic Rebirth, 1981-1989 (Fort Meade: National Security Agency Center for Cryptologic History, 1995b). p. 293.

2 Ibid.

3 Roger R. Schell, “Computer Security,” Air University Review (1979).

4 Warner, “Cybersecurity: A Pre-History.” p. 786.

Wargames and the 414s

‘Hacker’ used in mainstream media

The events leading to a nation-wide wake-up call took place in November 1979.1 A person “had mistakenly put military exercise tapes into the computer system” of the North American Air Defense Command (NORAD),2 which initiated an inadvertent injection of test scenario data “into the missile warning computers which generated false alerts”.3

That test scenario data simulated an all-out nuclear strike on United States mainland. The United States National Security Council was under the assumption that the Soviet Union had launched 220 missiles; a number that was later adjusted to 2.200 missiles.4 Close to the moment of requesting the President to decide on ordering a retaliatory strike, when “the Strategic Air Command was [already] launching its planes” a phone call was informed the National Security Council of NORAD’s error.5

The erroneous NORAD notification did not function as wake-up call however, though it did serve as the basis for the movie WarGames in 1983. The movie subsequently triggered “high school students from Milwaukee, inspired by WarGames and calling themselves the 414s” to prove that they could gain access to military networks.6 The 414s got nation-wide media attention, which resulted in the first use of ‘hacker’ in mainstream media and a year later in specific legislation in order to secure federal information systems.

1 Michael Warner, “Cybersecurity: A Pre-History,” Intelligence and National Security 27, no. 5 (2012), 781-799. p. 787.

2 Robert M. Gates, The Ultimate Insiders Story of Five Presidents and how they Won the Cold War (New York: Touchstone, 1996). p. 114.

3 United States General Accounting Office, NORAD’s Missile Warning System: What Went Wrong? (Washington: United States General Accounting Office, 1981). p. 13.

4 Gates, The Ultimate Insiders Story of Five Presidents. p. 114.

5 Gates, The Ultimate Insiders Story of Five Presidents. p. 114.

6 Michael Warner, “Cybersecurity: A Pre-History”. p. 787.

Cyberspace entering the fray

Cyberspace

William Gibson coined the term cyberspace in his sci-fi story ‘Burning Chrome’.1 He further defined cyberspace in his sci-fi book Neuromancer in 1984. He described cyberspace, in the context of his novel, as a “consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts. A graphic representation of data abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding”.2 The term “cyberspace serves as the mold from which a legion of neologisms are cast: cyberpunk, cyberculture, cyberlife, cybernauts, cyberselves, cybersex, cybersociety, cybertime – cybereverything”.3

He later stated: “All I knew about the word cyberspace when I coined it, was that it seemed like an effective buzzword. It seemed evocative and essentially meaningless. It was suggestive of something, but had no real semantic meaning, even for me, as I saw it emerge on the page.”4

1 William Gibson, “Burning Chrome,” Omni, July, 1982, 72. p. 72.

2 William Gibson, Neuromancer (New York: Berkley Publishing Group, 1984). PART two

3 Lance Strate, “The Varieties of Cyberspace: Problems in Definition and Delimitation,” Western Journal of Communication (Includes Communication Reports) 63, no. 3 (1999), 382-412. p. 382.

4 William Gibson: No Maps for these Territories, directed by Mark Neale (New York: Docurama Films, 2000)

Gulf war dubbed “information warfare”

See for instance:

Alan D. Campen, The First Information War: The Story of Communications, Computers, and Intelligence Systems in the Persian Gulf War (Fairfax: AFCEA International Press, 1992).

Cyberwar is Coming!

Netwar and cyberwar

While the military was institutionalizing the concept of information operations, the concept of cyberwar1 and netwar emerged in a 1993 report of the Research and Development Corporation (RAND).2Arquilla and Rondfeldt suggested two different species of ‘information mediated warfare’: cyberwar and netwar.3 The difference between the two lies in their nature, netwar is understood to be “refer to information-related conflict at a grand level between nations or societies […] it means trying to disrupt, damage, or modify what a target population ‘knows’ or thinks it knows about itself and the world around it”4 and cyberwar “refers to conducting, and preparing to conduct, military operations according to information-related principles”.5

Cyberwar is understood to be ‘war’ about knowledge, about who knows what, when, where and why, and about how secure a society or military is regarding its knowledge of itself and its adversaries”.6 This notion gained acceptance amongst the military, where it was, as intended by Arquilla and Ronfeldt, conceived to be an overarching concept of information operations.7

1 There are instances of ‘cyberwar’ usage before the report, see for instance: Eric H. Arnett, “Welcome to Hyperwar,” The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists 48 (1992), 14. p. 15.

2 John Arquilla and David Ronfeldt, “Cyberwar is Coming!” Comparative Strategy 12, no. 2 (1993), 141-165.

3 Arquilla and Ronfeldt, “Cyberwar is Coming!” , 141-165. p. 145.

4 Ibid. p. 146.

5 Ibid. p. 148.

6 Frans P. B. Osinga, Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd (Delft: Eburon Academic Publishers, 2005). p. 306.

7Richard Szafranski, “A Theory of Information Warfare: Preparing for 2020,” Airpower Journal (Spring, 1995).

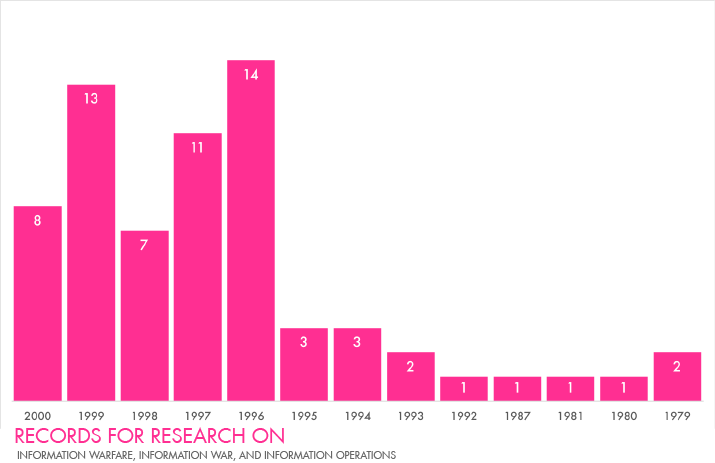

Information operations hype

information warfare command & control warfare

Information Operations

Information warfare was institutionalised in the U.S. with the creation of the Air Force Information Warfare Center (1993),1 the Fleet Information Warfare Center (1995)2 and the Army Land Information Warfare Activity (1995).3 By that time other States noticed these efforts made by the United States, consequently Boris Yeltsin deemed it “necessary to devote more attention to the development of the entire complex of the means of information warfare”.4 Similarly the Chinese noted in 1995: “In the near future, information warfare will control the form and future of war. We recognise this developmental trend of information warfare and see it as a driving force in the modernisation of China’s military and combat readiness. This trend will be highly critical to achieving victory in future wars”.5 In 1996, spearheaded by the United States Army, the United States adopted a less ‘belligerent’ notion, namely: ‘information operations’.6

1 Air Intelligence Agency, “Air Force Information Warfare Center,” Air Force Intelligence Agency Almanac, no. 97 (August, 1997a). p. 20; Dan Kuehl, “Joint Information Warfare: An Information-Age Paradigm for Jointness,” Strategic Forum Institute for National Strategic Studies, no. 105 (March, 1997). p. 2.

2 Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, OPNAV Instruction 3430.26: Implementing Instruction for Information Warfare/Command and Control Warfare (IW/C2W), 1995a). p. 8.

3 Richard A. Sizer, “Land Information Warfare Activity,” Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin (January-March, 1997).

4 James Adams, The Next World War: Computers are the Weapons and the Front Line is Everywhere (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2001). pp. 238, 239, 244.

5 Wang Pufeng, “The Challenge of Information Warfare,” in Chinese Views of Future Warfare, ed. Michael Pillsbury (Washington: National Defense University Press, 1998), 317-326. p. 318.

6 United States Army, Field Manual no. 100-6: Information Operations (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1996).

Cyber everything!

Whitepapers and ‘the Cyber’

The United States government spearheaded a change in direction – some would argue in the wrong direction – by issuing Executive Order 13010.1 ‘Cyber threats’ were identified in the realm of critical infrastructure protection and understood to comprise “electronic, radio-frequency, or computer-based attacks on the information or communications components that control critical infrastructures”.2 Subsequently, in a similar vein of the protection of critical infrastructure, Presidential Decision Directive 63 earmarked “cyber-based information systems” besides critical infrastructure.3 The Decision Directive 63 also outfitted other terms with a cyber prefix, being: “cyber attacks”, “cyber supported infrastructures”, “cyber systems”, “cyber-based systems” and “cyber information warfare threat”.4 Despite coining these various neologies, the document does not define these terms.

The next document by the United States government aimed at safeguarding information systems – in this case without a cyber-prefix – is the document “Defending America’s Cyberspace, National Plan for Information Systems Protection”.5 This document spawned 33 new cyber-prefixed notions and placed them in a context of national security.6 The only two cyber-terms defined, however, are cyberattack (“Exploitation of the software vulnerabilities of information technology-based control components”) and cyberspace (“describes the world of connected computers and the society that surrounds them […] commonly known as the INTERNET”).7 The meagre definition section leaves much issues unresolved, but from the tone, context and the two definitions one could argue that cyber in the document has shifted from a broad concept as intended by Arquilla and Ronfeldt to a narrow concept related to computer and network mediated issues.

1 William J. Clinton, “Executive Order 13010: Critical Infrastructure Protection,” Federal Register 61, no. 138 (1996), 37347-37350.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 The White House, Securing America’s Cyberspace, National Plan for Information Systems Protection: An Invitation to a Dialogue (Washington, DC: The White House, 2000).

6 The new notions: “cyber vulnerabilities”, “cyber disruptions”, “cyber defense”, “cyber networks”, “cyber-intrusions”, “cyber-security”, “cyber incidents”, “non-cyber systems”, “cyber technology”, “cyber-ethics”, “Cyber Citizens Program”, “cyber-driven systems”, “cyber criminals”, “cyber events”, “cyber-burglar tool kits”, “cyber intruders”, “cyber warfare”, “cyber status”, “cyber resource guides”, “cyber-reconstitution”, “cyber assurance”, “cyber literacy”, “cyber dimensions”, “cyber sensors and intrusion detection systems”, “cyber situation understanding”, “cyber systems command and control tools”, “cyber defense strategies”, “cyber crisis”, “cyber disruptions” and “cyber nation”.

7 The White House, Securing America’s Cyberspace. p. 146.

Integration of Computer Network Attack (CNA)

Computer Network Defense, CND (1998)+Computer Network Attack, CNA(2000) = Computer Network Operations, CNO(2001)

“Joint Task Force-Computer Network Defense (JTF-CND) reached initial operational capability on Dec. 30, 1998, after exercises and real-world events demonstrated the need for a single coordinating agency with the authority to direct actions necessary for the protection of the Defense Information Infrastructure (DII).

Under the Unified Command Plan 1999 (UCP 99), effective Oct. 1, 1999, the President assigned the CND mission to the U.S. Space Command (USSPACECOM), with the JTF-CND as the subordinate command responsible for executing CND operations.

UCP-99 also designated USSPACECOM as the military lead for Computer Network Attack (CNA) effective Oct. 1, 2000. The USSPACECOM Deputy Director of Operations-Computer Network Attack (DDO-CNA) served as the initial focal point for the CNA mission.

In December 2000, USCINCSPACE directed his staff to assess the feasibility of combining specific aspects of CND and CNA under a single operational commander.

The intent behind the consolidation was to operationalize CND and CNA and fully integrate those capabilities with air, land, sea and space forces across the full spectrum of conflict. Effective April 2, 2001, JTF-CND was re-designated Joint Task Force-Computer Network Operations (JTF-CNO). Effective Oct. 1, 2002, JTF-CNO was assigned to the commander, U.S. Strategic Command.”1

1 U.S. Strategic Command Public Affairs. (2003). Joint Task Force – Computer Network Operations. Retrieved from iwar.org.uk/iwar/resources/JIOC/computer-network-operations.htm

Cyberspace the Fifth Warfighting Domain

Integration of Cyberspace as Warfighting Domain

The 2004 National Military Strategy of the United States mentioned cyberspace in the context of conventional war fighting domains, it stated, “the Armed Forces must have the ability to operate across the air, land, sea, space and cyberspace domains of the battlespace”.1 Cyberspace was, however, only explicitly earmarked as fifth warfighting domain in 2006 and defined as “a man-made domain” that is “characterised by the use of electronics and the electromagnetic spectrum to store, modify, and exchange data via networked systems and associated physical infrastructures”.2 Thus, 2006 marked the militarisation of cyberspace in the United States and other States have followed since. The notion of cyberspace has remained largely unchanged and has been adopted by other States and institutions.3

1 The Joint Chiefs of Staff, The National Military Strategy of the United States of America: A Strategy for Today; A Vision for Tomorrow (Washington, DC: Office of the Chairman, 2004). p. 18.

2 The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, The National Military Strategy for Cyberspace Operations (Washington, DC: Office of the Chairman, 2006b). p. 3.

3 See for instance: Michael N. Schmitt, Tallinn Manual 2.0 on the International Law Applicable to Cyber Operations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017); The Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication 3-12 (R): Cyberspace Operations (Washington, D.C.: The Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2013b). pp. v-vi.